A journey into the depth of dream

Meir Ahronson

Daniella Sheinman’s works are laid on the floor in a studio located in a large hangar in a moshav (cooperative settlement) in central Israel. This is the first time I visit Sheinman in this studio. Years ago I visited her in the studio she had in the basement of her private home, and she showed me long canvas scrolls in full due to the space limitations. Despite the harsh viewing conditions, there was something about those works that captured my attention. They attested to a type of Sisyphean, persistent work that unfolded over many meter of canvas. Moreover, they exhibited a measure of determination. Confrontation of such large canvases requires neutralization of the desire to see the finished product. There is a quantifiable commitment in such practice.

It has been a long while since, and the works I saw this time were nothing like those other works back then. Some time ago Sheinman sent me the catalogue of an exhibition she has had in respectable bank in Germany, where she mounted a large scale installation consisting of wooden lattice, large drawings and sculptural elements incorporated throughout. That work, which traveled from the bank to the Ludwig Museum im Deutchherrenhaus, Koblenz, was the origin of the work I saw when I entered Sheinman’s present studio. When I looked at the canvases, I recalled an excerpt from a letter written by French novelist Gustav Flaubert to Louise Colet on January 16, 1852:

“The finest works of art are those in which there is the least matter. The closer expression comes to thought, the more the word clings to the idea and disappears, the more beautiful the work of art”.

Sheinman’s early paintings, in the period that preceded the aforementioned scrolls, were highly colorful and expressive. They were comprised of figures and colors stains, and incorporated a readable narrative.

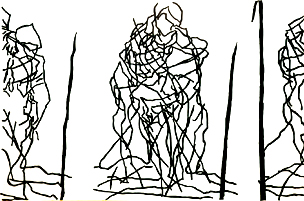

Surprisingly, the painting became a type of dilution that calls to mind the principles of homeopathy. The principal substance is thinned to the point of non presence, and a new substance is obtained in its stead that carries the qualities of the original substance, yet is typified by such a degree of dilution that the poison transforms into a healing potion. Drawing has come to replace painting. Rawness itself has become a value independent of manifestation.

And what does the eye see? It sees the lines transforming into latticed grids, bars curving into organic forms; figures losing and re- acquiring form. It observes an extensive surface where the gaze is set free.

In Sheinman’s OEUVRE one can consistently identify how the artist uses traditional means to generate painting that is modern and current in essence. In these paintings presented to us there, the gap between the world of imagination and visual phenomena on one hand, and the exposed world of reality on the other, Is highly manifest. Despite Its title and definition, it is a world invisible to the viewer who is unfamiliar with the artist’s inner reality. The sights presented to us by Sheinman can be grasped only by exposing the world that motivates her to work with canvas and graphite pencil. It is clear to us that elsewhere in the world mothers would not have made anxious painting such as the early works by Sheinman the mother, or, for that matter, any other Israeliness itself, then when coming to explore Sheinman’s works one must certainly be aware of her Israeliness in particular, and her affinities to the world of art in general.

Daniella Sheinman

Daniella Sheinman