Arachne’s Woof: Women, Creativity and History

Dr. Kathy Battista

In Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the goddess Minerva (the Greek deity of war and wisdom as well as the patron of weaving and embroidery) takes exception to the hubris of the mortal Arachne, a poor country girl who defiantly claims to be the superior weaver. Minerva, disguised as an old woman, appears to Arachne and suggests that the mortal offer forgiveness. When Arachne boastfully refuses, Minerva reveals herself and challenges the girl to a weaving contest. Minerva weaves a tapestry that depicts scenes of the greatness of the gods, including her own victory over Neptune. Arachne’s tapestry illustrates a much different point of view: a skillfully woven portrait of gods raping and deceiving humans. Minerva flies into a rage over Arachne’s skill and beats her, prompting the mortal to hang herself, and Minerva eventually turns Arachne into a spider, thus relegating her to a life of spinning webs. Ovid writes of this moment: Read More

In Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the goddess Minerva (the Greek deity of war and wisdom as well as the patron of weaving and embroidery) takes exception to the hubris of the mortal Arachne, a poor country girl who defiantly claims to be the superior weaver. Minerva, disguised as an old woman, appears to Arachne and suggests that the mortal offer forgiveness. When Arachne boastfully refuses, Minerva reveals herself and challenges the girl to a weaving contest. Minerva weaves a tapestry that depicts scenes of the greatness of the gods, including her own victory over Neptune. Arachne’s tapestry illustrates a much different point of view: a skillfully woven portrait of gods raping and deceiving humans. Minerva flies into a rage over Arachne’s skill and beats her, prompting the mortal to hang herself, and Minerva eventually turns Arachne into a spider, thus relegating her to a life of spinning webs. Ovid writes of this moment: Read More

Special Exhibition – Daniella Sheinman, String Line

By Howard Rutkowski

Having studied painting and sculpture at the Belazel Academy of Art and Design in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv’s Avni Institute of Art and Design, Daniella Sheinman’s first works reflected a more conservative approach to figurative works, very much in the European modernist tradition. These were competent works, utilizing a strong sense of color and line, but were not ground-breaking in any sense. That all changed when Sheinman abandoned figurative imagery and undertook the path towards abstraction.

Having studied painting and sculpture at the Belazel Academy of Art and Design in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv’s Avni Institute of Art and Design, Daniella Sheinman’s first works reflected a more conservative approach to figurative works, very much in the European modernist tradition. These were competent works, utilizing a strong sense of color and line, but were not ground-breaking in any sense. That all changed when Sheinman abandoned figurative imagery and undertook the path towards abstraction.

Through abstraction, the narratives – implied or otherwise – inherent with figuration are given over to a focus on materials, surface and form. In many ways it is a reduction, challenging both artist and viewer to go beyond the immediately recognizable and to concentrate on the application of line or color to find the expressed ideas. It is a notoriously difficult approach that, in the wrong hands can easily disappoint , with results that are merely decorative. However, Sheinman’s forays in this direction allowed her control of line and color to come forth, resulting in more powerful imagery and an interplay of line and pattern.

The early abstract pieces are bold and carefully constructed with a very direct visual impact. They are like declarative sentences that communicate without hesitation what the artist was crafting. Over time, these works, too, evolved into more spontaneous, more gestural compositions where the experimentation with different materials becomes more integrated. The use of new materials and support structures allowed the artist to explore new approaches with space and taking a very big risk in abandoning color – often the unifying component to painting – Sheinman was able to bring her work from a traditional, two-dimensional presentation to one that would harness the environment where the work was displayed. Read More

Daniella Sheinman / String Line

Daniella Talmor

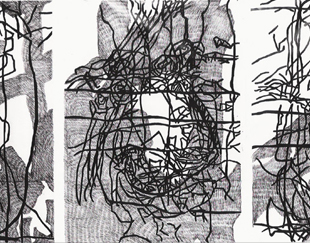

At the outset of her artistic career, Daniella Sheinman created colorful figurative paintings, but over the years, her paintings became monochromatic and free. Most of the works in the current exhibition are executed in black graphite on large-scale raw white canvases. They express the unique, personal and impressive language that the artist has developed during the past two decades – a language that is abstract, yet at the same time firmly constructed and meticulously designed.

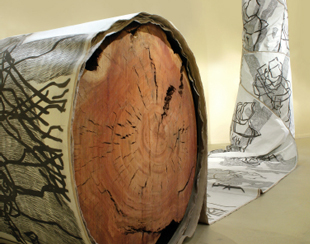

At first glance, the works in the exhibition look spontaneous but they are, in fact, the product of precise, careful planning and Sisyphean labor with thick graphite lines. It is interesting to trace the process by which they are created. First, Sheinman created spontaneous and unmediated preparatory sketches in pencil on paper. Next, she photographed the sketches and printed them on slides, from which she built the desired image, sometimes through assembling the slides one on top of the other, either fully or partially overlapping each other. She then projected the chosen composition onto very large canvases in her spacious studio and sketched in the contour lines. In the final stage, she filled in the contour lines with dense graphite lines that all merged together as a black surface. During the work of filling in, the large pieces of canvas were rolled up and laid on the studio’s table, with only a small section left exposed to work on. The work of filling in was slow and laborious, and it was only at the end that the fabric was fully unrolled to reveal the complete artwork. From this standpoint, the artist’s work recalls that of printmakers, whose creations are wholly revealed only at the end of work process.

Ugo Rundinone at the Sommer Contemporary Art Gallery, Daniella Sheinman at the Litvak, and a group show at Alon Segev

From: The Window, an art blog by Smadar Sheffi. Originally posted on September 7, 2013

Daniella Sheinman’s installation, String Line (exhibited along with a small video installation by Nivi Alroy) reflects the Litvak Gallery’s change in direction, as well as denoting a significant development in Sheinman’s oeuvre. Her language has undergone a process of reduction and distillation. Stripped of human figures and color, Sheinman develops systems of black lines, which she also used in the past, into complex meshes. They refer perhaps to nature, recognizable as landscape (bushes and trees) or perhaps cellular structures, hugely enlarged. She draws with graphite on canvas and paper, and, together with cylinders made of plexiglas set up in the gallery, has created a formal, non-narrative space with momentum, interest, and a great degree of elegance.

Israeli Venus in Germany

Eran Tifenborn, Berlin. Yedioth Ahronot 22 June 1999. Israeli artist Daniela Sheinman plays with life and death across the ocean

The exhibition of the Israeli artist is making waves in Germany.

Daniella Sheinman, a resident of Ramat Efal, was invited to present the exhibit, “Interior space” in Koblenz, near Frankfurt, and visitors to the exhibit can not remain indifferent.

Sheinman is a guest artist at the Ludwig Museum, one of the most highly respected collections in Europe. The museum’s branches are scattered throughout the cultural centers on the continent, and it is claimed to be standard- setter in the art world.

Sheinman’s exhibit deals with life. In this way Sheinman “hit the Germans over the head with a 5 kilo hammer”, in the language of one visitor.

The artistic treatment of Germany by Jewish artists is typically connected to death, due to understandable historical reasons.

Sheinman’s exhibit was a surprise in that she chose life from a fascinating perspective; the borders of life, or, more accurately, what can be said about life from an external point of view, from the point of view of death.

The installation,’ Interior Space’ is spread over a large floor space in the museum. On the top floor Sheinman displayed three private Variations on the famous Botticelli painting, ‘Venus Rising from Sea’. Sheinman’s Venus appears on three canvases light blue, green and pink- purple.

The exhibit, as well as Sheinman’s artistic path, was followed by former Prime Minister Shimon Peres who also dedicated a text in the catalog.

Whoever hurries can still catch the exhibit until 4th of July.

Shutting one eye

Uzi Tzur. Haaret'z, June 26 1998

within Sotheby’s new display space. A space encompassed within a space, maintaining full command of the internal space she created.

In contrast to other exhibits, this one excels in Its simplicity and clarity. It is portrayed neither theatrically nor dramatically but rather by uniform brightness. The exhibit succeeds in combining a two dimensional impression with a three – dimensional non aggressive sculptural environment into an overall creation spectacularly designed, aesthetic but not over decorative, with an air of overbearing clean, lit radiance. It is unfortunate that the exhibition is scheduled to close after such a period.

Pushed from Paradise into Chaos

Lieselotte sauer-kaulbach "Interior Space" and "Venus - Project" Installation of Daniella Sheinman in the Ludwig Museum

The Installation “Interior space” of the Israeli artist Daniella Sheinman, who “captivates” the observer in the Ludwig Museum. When he has entered the room, he is already part of the slat labyrinth, which seems to want to keep him away from friezes of unusual monumental drawings on the walls – and forces him together with them which shows him his path, but when blocks this way with obstacles and barricades which restricts him like a prison- but also leaves him all freedom, also the one of the view.

Out of this silence the observer as well as the artist find back from destruction to a peaceful together, out of which new life starts. Is there a return to paradise after such a lot of sorrow? After so much fight a idyllic happy end? This would then be too hypocritical. And that is why Daniella Sheinman steers in another direction again, breaks up the idyll – Breaking up, which leads back to the beginning – end, which is beginning again.

Meaning of life

by Beate Reifenscheid. 1998, Ludwig Museum in Deutschherrenhaus

In Daniella Sheinman’s installation Interior space however, confinement, fear, chaos and terror prevail. As soon as the visitor enters the installation in order to perceive its implicit order, he is locked inside the cage. He becomes a victim of his desire for intuition. He will realize too late that he is not the distanced spectator of someone else’s story, but a witness to something that turns out to be his personal biography.

This ambivalence between the general and individual can also be found in the drawings of the cycle, which skillfully reclaim a realm between pure abstraction and referential figuration.

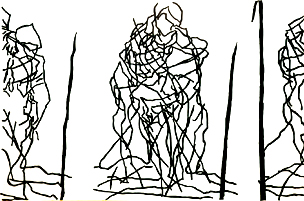

Daniella Sheinman’s cycle does not begin in the Garden of Eden, in paradise. It starts with the fall of Man, the loss of innocence and the subsequent expulsion from paradise. It opens with a thunderbolt, announcing agitation and inner conflict as a leitmotif. In the first two drawings, figures are depicted inside a rectangle symbolizing a door or gate. In the third drawing the theme of the expulsion becomes manifest: Adam covers his face and walks with his head bowed in shame. The echo like repetition of the figures of Adam and eve is accompanied by the recurrent motif of a gate that is gradually poised and threatening to fall. In the initial eight drawings Daniella Sheinman depicts the expulsion from paradise no less than six times. Entangled in a dense grid of lines, the characters seem to be alienated or imprisoned in a web. Read More

The lace Unstitcher

Aya Lurie

In her 1991 painting Mythical Clouds, Daniella Sheinman depicted her soldier son with a storm of expressive color stains and wiggly black lines raging around him.

At the bottom of the work she drew hands dragging smears of red paint.

Sketched on young soldier’s chest was a square black outline, and in it – a curved spiral. While this pattern recurs throughout the work, running across it like an ornament – design, when it is thus delineated on the soldier’s chest it looks like a target. Feeling of anxiety and chaos bustle around the son’s painted figure; these combine with the knowledge about the atrocities and horrors that engulf him, making him a part of them. The painterly affinity between those interwoven arrays of dense black lines sprouting in the 1991 piece Mythical Clouds and the current works featured in this show is formally conspicuous, despite a manifest reduction that distinguishes between those past works and the present ones. The female point of view – the mother’s cry vis -a vis her son’s whereabouts- leads in the current works to the obliteration of narrative (the son’s figure), color (the expressive articulation) and texture. This may attest to the artist’s having arrived at a stage of meticulous exhaustion of her work process, or perhaps indicate that the anxiety of loss is almost indescribable.

A journey into the depth of dream

Meir Ahronson

Daniella Sheinman’s works are laid on the floor in a studio located in a large hangar in a moshav (cooperative settlement) in central Israel. This is the first time I visit Sheinman in this studio. Years ago I visited her in the studio she had in the basement of her private home, and she showed me long canvas scrolls in full due to the space limitations. Despite the harsh viewing conditions, there was something about those works that captured my attention. They attested to a type of Sisyphean, persistent work that unfolded over many meter of canvas. Moreover, they exhibited a measure of determination. Confrontation of such large canvases requires neutralization of the desire to see the finished product. There is a quantifiable commitment in such practice.

It has been a long while since, and the works I saw this time were nothing like those other works back then. Some time ago Sheinman sent me the catalogue of an exhibition she has had in respectable bank in Germany, where she mounted a large scale installation consisting of wooden lattice, large drawings and sculptural elements incorporated throughout. That work, which traveled from the bank to the Ludwig Museum im Deutchherrenhaus, Koblenz, was the origin of the work I saw when I entered Sheinman’s present studio. When I looked at the canvases, I recalled an excerpt from a letter written by French novelist Gustav Flaubert to Louise Colet on January 16, 1852:

Daniella Sheinman

Daniella Sheinman